LACCTiC

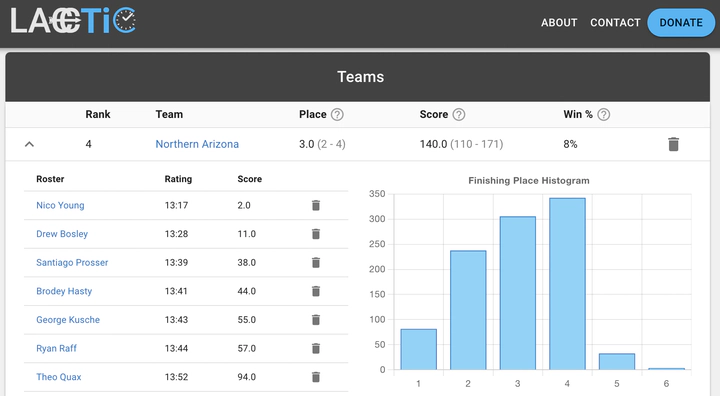

LACCTiC.com is a website that I developed in 2021 to convert cross country performances from varying course difficulties to their track 5k equivalents. The results are used to provide sophisticated rankings and race simulations. The aglorithm has evoled over time and has many small tweaks, but I will provide a short summary of the ideas here.

The main idea behind LACCTiC is to look at how finish times change across different courses. This won’t be informative for a single runner, who may have had a good and bad race. However, the average across many runners should give an idea of the course’s relative difficulty since the same number of people will have had good races and bad races.

Consider

First, suppose you knew everyone’s average 5k finesses, e.g.,

We will call

Now, suppose we knew all of the course adjustments (

We alternate between these two computations. Calculating the

Once we converge on solutions, we need to make sure that adjusted cross country season PRs line up with track PRs (we only used track PRs as an initial guess). To do this, we shift everyone’s adjustments and scores so that (on average) people’s best converted times equate to their track PRs. Of course, some people will be better than track and some will be worse.

A detail I’ve left out here is that not all runners run every course! If you go back through the equations, you should find that none of them require full participation from every runner. However, in order to get good results, we need to not have any “islands,” such as conferences that only race themselves and never have any comparison to the outside world.